In recent years independent and “print on demand” publishing has challenged the traditional publishing industry and opened a medium for thousands of “content creators” who self-publish and create their own work and make it available directly to their end consumer. Popular culture tells us that anyone can become a YouTube sensation and quit their day job to do what they love. Of course, very few actually get that kind of traffic and ad revenue, but the fact remains that the internet has produced a very decentralized publishing format for a variety of mediums. One such medium, aimed at fiction writers rather than video producers, is Wattpad.

0 Comments

Writing can be a lonely pursuit. On good days, it’s you and your story, peopled with interesting characters and exciting plot lines. On bad days, it’s just you and a blank screen, the blinking cursor mocking you for your haughty ideas about “being a writer.” Oh, that cursor!

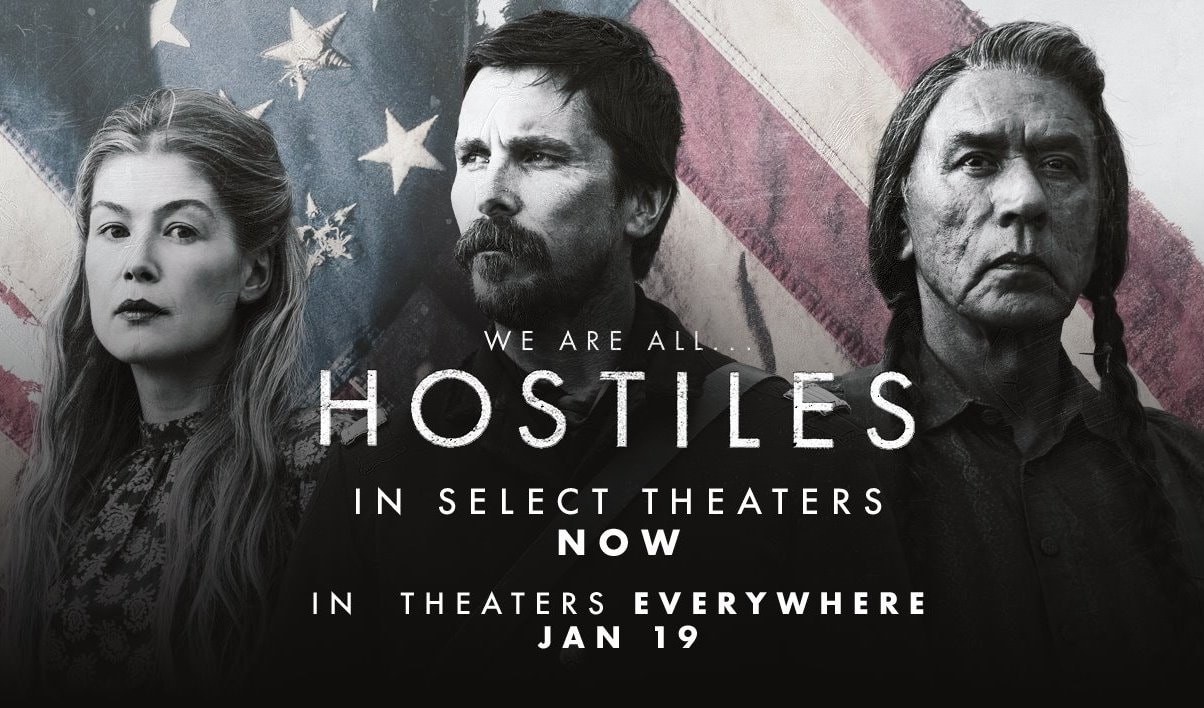

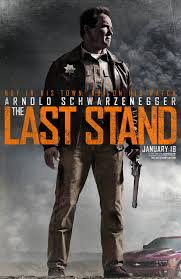

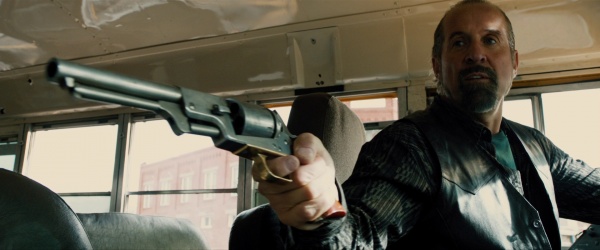

So writers must find like-minded people where they can, to provide community, guidance, editing, and moral support. Enter Scott Harris. Author of the award-winning Coyote Canyon series of western novels, Harris came up with a brilliant idea to bring together a bunch (51, to be exact) of his friends and acquaintances to write a series of short-short stories, each answering the same prompt. His first prompt was an iconic “A shot rang out!” - every story had two requirements; it must begin with this prompt, and it must be 500 words. Now, 500 words is a very short story, so it offers writers a certain challenge indeed! We all submitted our stories, and the final product is available on Amazon at the link below. It was well received, making the top 20 list in its first week as a new release! It’s a bit of a fascinating exercise to see how different 52 stories can be that all begin with the same 17 words, and I encourage everyone to go check it out. When you like it, keep an eye out for the next installment, as this will be a regular feature running on a quarterly basis - 52 authors, 500 words, but a different commonality each time!  Hostiles is a great western. According to the previews, an early reviewer declares it this generation’s Unforgiven, and perhaps it is. The movie is deceptively simple, but there is much going on “behind the scenes,” and the film is rich in layers of meaning. I won’t give away too much; perhaps in a few months I’ll do a more complete analysis, but for now just go see the film. Hostiles is a classic western, and addresses the classic western themes of captivity and savagery. At its core, Hostiles is essentially a captivity narrative. The plot centers on the primary captivity of the aging Cheyenne Chief Yellow Hawk (Wes Studi) and his family, who have been held prisoner for 7 years. Yellow Hawk is now near death and has been granted his request to be returned to his native homeland to die, and his long time nemesis Capt. Joseph J. Blocker (Christian Bale) is assigned the detail. But the movie does a marvelous job of examining all manner of captivities for many of the characters. Capt. Blocker says in an early scene that “every time we lay our heads down out here, we’re prisoners,” and indeed, this remark proves prophetic. Chief Yellow Hawk is a literal captive, being escorted in chains, and in turn Capt. Blocker is held captive by his duty and obligation to escort and protect his sworn enemy. Sgt. Charles Willis (Ben Foster) is literally a prisoner, and in spite of being a U.S. soldier he finds himself held in a captivity even more severe than the “savages” he’s traveling with. Rosalie Quaid (Rosamund Pike) is held captive by the trauma she endures in the opening scene, and Capt. Blocker and his entire detail are held captive by their duty to assist her. Msgt. Thomas Metz (Rory Cochrane) is held captive by his “melancholia.” And finally, the entire detail is held captive by the savage Comanche who threaten them throughout the film. This captivity is central to the overall theme and connects viewers to the theme of savagery, which permeates the film. The film destabilizes the issue of savagery almost immediately with the character of Jeremiah Wilks (Bill Camp), a Harper’s Bazaar writer who asks Capt. Blocker if it’s true that he has taken more scalps than Crazy Horse himself. Capt. Blocker defines Chief Yellow Hawk’s savagery by his brutal treatment of foes and prisoners, but it quickly becomes apparent that the Capt. has as brutal a history as his opponent, begging the question of how savagery is defined. Savagery is clearly demonstrated in the opening scene by the Indian attack, and when Mrs. Quaid is brought to the Army detail’s camp, she is upset by the appearance of the native prisoners - they are racially identified as “savage.” But shortly thereafter, the wife reaches out to her, and her status as a savage is destabilized through her charitable action. In the same vein, when the entire party is threatened by the Comanche, the Cheyenne Chief Yellow Hawk tells Capt Blocker that “these people are rattlesnake people” and are dangerous, that they will not discriminate, and will kill them all. Yellow Hawk’s message to Capt. Blocker throughout the film is that they must work together against a common enemy. Their Army prisoner Sgt. Charles Willis (Ben Foster) appeals to the Capt.’s sense of common enemies in a different way, pleading for mercy and arguing that his guilt is no greater than the Capt.’s or any other Army soldiers’ from that time. His argument is that they are all guilty, essentially that they are all savages, and it is hypocritical to condemn him for crimes that are fundamentally no different from what others have committed, yet he should hang while others go free. Capt. Blocker says only “I was doing my job,” thus falling back on his commitment and the captivity of his will and conscience to the demands of his duty, wholly sidestepping the question of his savagery. The definition of “savage” is destabilized by several characters across several scenes, and in fact the movie directly addresses the “Indian question” through both its plot and the dialogue of several characters. I have seen various people on social media criticizing the film for its “liberal” bias, but I found their criticisms ill-founded. The dialogue representing differing perspectives on how natives should be treated by the govt, by the army, and who represents the real savage are all questions that were being actively debated in the late nineteenth century, and the film does justice to its characters, subject, and its viewers by presenting fully fleshed out characters facing a complicated period of history.  Some time ago (geez, almost a year ago?!) I posted a blog entry about my bowie knives, promising to cover the group individually in some detail. So here we go with the second installment as I go through my “collection” (I can’t bring myself to call it that without the ironic quotations), beginning with the most “frontier” of my knives. Firstly is the largest of the group, a semi-custom by Plowshare Forge. I say “semi-custom” because it’s a standard catalog item for the maker, but it’s also a handmade item that isn’t made until you order it, and you can make specific requests, so in that respect it’s custom. Plowshare Forge specializes in the rough and tumble world of “frontier” blades, blades that recreate the knives that our cowboys, or our doughboys and GIs would have had made for them by local smiths and actually carried into battle. No high polish sheen here; these are hard core working blades, and he intends them to look the part. This knife is a Musso Bowie, so named because the original upon which this is based was owned by a Joseph Musso. He claimed this knife was THE knife owned by Bowie himself, which nearly all scholars dispute, but it’s still a super cool knife, which, in the world of Bowie knives, counts for at least as much as historical authenticity. As they say in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, “when the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” The Musso bowie is almost certainly not the blade that James Bowie actually carried in his famous Sandbar Duel . . . but it’s what he should have had. For those of you keeping score, this is the knife Emmett carries in my novel The Ballad of the Laurie Swain. It’s big and bold, just like Emmett himself. The blade is nearly 13 inches long, and almost 3 inches wide. It has a large “S” guard and a strip of brass which runs almost the full length of the spine of the blade. This brass strip has been the subject of some discussion in Bowie circles; I originally heard that it was supposed to be for parrying in knife dueling, with the idea that the soft brass would “catch” the opponent’s blade and open him up to a counter attack. I don’t buy the “blade catcher” story, but I do think the brass strip is designed for parrying; the softer brass would absorb the shock of the blow and protect the more brittle (and more expensive) steel beneath. Higher end knives often have a differential temper, in which the spine is softer than the edge, to accomplish the same thing, but that’s an awful lot to expect of a frontier blacksmith. Do you remember the Bowie quote about what his knife should do? Sharp enough to shave, broad enough to use as a paddle, heavy enough to chop like an ax, long enough to cut like a sword . . . when one thinks of all those requirements, this knife embodies it all. This blade is impressive. It’s large and feels heavy. The blade is not unduly thick, but the point of balance is far forward, about a solid 3 inches from the crossguard. This balance point makes the knife feel very blade-heavy, and it handles like a saber in the hand. This is neither good nor bad, just an idiosyncrasy of the blade that differentiates it from others. As a woods blade, a frontier knife depended upon to do camp chores (or row a small boat!) such a weight forward balance is an asset - it makes the knife a better chopper for cutting kindling or even making a shelter - this is the chopping like an ax part of Bowie’s famous recipe. As for a fighting knife . . . well, such a forward balance point makes it slower in the hand. Whether or not that would be a liability would depend heavily on what sort of weapon one were facing. If it were a saber, spear or lance, then not so much. If it were a lighter, faster knife, it could be a problem. One issue I have with the design is the tip. It is SO thin and narrow! In some respects this is perhaps not a problem, and it is certainly an intentional design. The tip has a dramatic upward sweep the terminates in a narrow tip that rises above the center line. Combatively, this is designed to facilitate a back cut, as the top swedge of the blade is sharpened. This is purely a combat feature; not only is not necessary in a field knife, but it could actually be a liability, as it creates an additional edge that can cut the user if one is inattentive. Small, fine woodcraft cutting tasks become more complicated when the upper edge is sharp. Also from a combative perspective, the tip is swept too far up to make an effective thrusting design; the actual tip only works when thrust along an arcing line, as in a back cut. In a straight thrust the point doesn’t pierce as effectively as it could, leaving it to the belly of the blade to cut its way in. It’s certainly capable of a straight thrust, but this would force the knife to work against its own natural edge geometry and it wouldn’t pierce with nearly the efficacy that it could if the tip were positioned differently. So my beef with this design centers on that narrow, narrow tip. It is, in my opinion, structurally weak. While such a narrow tip ought to be good for thrusting, this one really isn’t because the tip is pointing up and off the center line. And I can’t imagine trusting this skinny tip to hold up under any sort of hard use, especially lateral forces on the tip, whether that force is from prying dead wood from a log for kindling, or getting one’s tip stuck in the ribs of a human adversary (not that this is an issue for me). For fans, this pattern of knife is offered under the general title “primitive bowie” from places like Atlanta Cutlery and its ilk. More recently, a highly polished version of this knife is featured in the film series The Expendables. It is thrown to great combative effectiveness (don’t even get me started… perhaps I’ll write a separate blog just about throwing knives). Still, this knife represents what a combat blade ought to be to a large percentage of the (probably male) viewership, and it certainly represents the epitome of a large frontier bowie knife. To get your own: Plowshare Forge: http://plowshareforgeknives.blogspot.com/2009/07/musso-bowie.html Expendables Bowie: http://www.budk.com/Gil-Hibben-Expendables-Bowie-Knife-with-Sheath-16631  Okay, so this title is a bit grandiose and frankly a cheap titillation to get you to read my review. I’m leery of superlatives like this anyway, but the upshot is that Forsaken is a damned fine western, and I will say it’s one of the best of the breed. It helps that it has some fine actors, most notably Keifer Sutherland playing the son of real-life father Donald Sutherland. This made news as the first film in which both men acted opposite one another, and their performances make me hope they do so again. Also notable are Demi Moore in the role of Mary Ellen, and Micheal Wincott as Gentleman Dave. The action opens with John Henry Clayton returning to his old home to a cold reception by his father Reverend Clayton. His mother has passed away, and the Reverend doesn’t take pains to hide his opinion of his “gunman” son. John Henry left for the Civil War with promises to return to his family, and to his love Mary Ellen, but has been gone for years, with nothing but dramatic tales of his violent exploits returning home on his behalf. Here is already a classic western motif, the Civil War soldier who was so scarred by battle that by the war’s end he knows no other life than one of violence. John Henry claims to have put his guns away, which is also a standard motif for the gunfighter in many films. His father has doubts, as do we, because of course, a peaceful man does not a western movie make. As you might expect, there is a greedy rancher named James McCurdy (played by Brian Cox) who is forcefully buying up all the nearby properties, offering reasonable (or less so) payments, and bullying and forcing sales through violence when necessary. Early in the film, John Henry meets his antagonists in the saloon, where he has gone to get a soft drink. This scene plays out very similarly to the classic western Shane, which features a soda-drinking hero. As an aside, Eastwood reprises this to a smaller extent in Unforgiven with the shootist who has given up drinking. Here he meets Gentleman Dave, played by Michael Wincott. The other gun hands think John Henry is going to be a pushover, but Gentleman Dave recognizes John Henry for who he is, and is not distracted by his apparent nonviolence. The Gentleman Dave character seems to me to be modeled on a Doc Holliday mold, and I am eager to see what else Wincott has played, or may play in the future. Gentleman Dave is a hired gun, and is not afraid to shoot people, but he also distinguishes himself as being a businessman rather than simply bloodthirsty. Forsaken follows a fairly genre standard approach in which John Henry stands up for a homesteader who is being bullied in town by McCurdy’s men. He is beaten, but refuses to become violent himself. This nonviolence will be tested, of course, and when McCurdy’s mean stab Reverend Clayton John Henry straps his guns on again. He carries a Colt (of course), but before he heads to the saloon to confront McCurdy and his men he also stops in a gunshop and buys a second weapon. Forgive my geeking out here, but he buys a LeMat, which was a French-made revolver that was used by the Confederacy during the Civil War. It’s an impressive piece, with a nine shot cylinder and a 20 gauge shotgun barrel underneath the primary barrel. The inclusion of this piece is something of a historical anomaly, as these pistols were fairly rare and by the time of this film it would’ve been a highly unlikely choice for a secondhand purchase - but I’ll give it to them just because seeing one on film delighted me. The fight ensues, and it’s a top-shelf, bar-jumping, table flipping movie gun battle. I won’t spoil too much, except to say that before it’s all over, only McCurdy himself (barricaded upstairs) and Gentleman Dave remain. Gentleman Dave and John Henry find themselves on the street in what is shaping up to be a classic “high noon” kind of showdown. John Henry tells Dave that he has no fight with him, that he could just walk away. Gentleman Dave counters that he accepted a contract with McCurdy, and his reputation would be ruined if he abandoned a client. John Henry notes that he’s down to his LeMat, which is heavy and gives Dave an unfair advantage; he asks leave to go fetch his Colt. Dave assents, and John Henry goes inside to get it. While there he encounters McCurdy and kills him, leaving only Gentleman Dave standing. Here’s where the film subverts the audience expectations - now that his boss is dead, Gentleman Dave is free to walk away from the fight, and he does exactly this. I think this is a brilliant twist on the genre and elevates this film above many others who simply tick off genre staples in predictable ways. Finally, there is Mary Ellen, played by Demi Moore. She plays this nicely, with understated makeup - while she is still a beautiful woman, she very much looks the part of an older frontier woman; the film resists the impulse to make her too beautiful. She is married, having tired of waiting for John Henry to return, and the couple dance with the romantic tension that remains between them throughout the film. Theirs is a beautiful story of unrequited love. So Forsaken may not be the best western ever, but it’s certainly one worth watching, and if you’re a fan of the genre, probably owning. Go to Amazon and buy it now! amzn.to/2ppjxPH  Photo from IMFDB.org Photo from IMFDB.org I was reading an article by Lily Absinthe on the costuming of one of my favorite films, Tombstone (https://lilyabsinthe.wordpress.com/2015/05/31/). In it she predictably points out where the film gets costumes right and wrong based on actual period clothing, but where she surprises me is in her observation that moviemakers ought to be given a bit of leeway in their choices, because as she concedes, “Costuming supports this story-telling process and it’s often subject to conscious design changes in order to increase the dramatic effect.” For reasons I dare not contemplate, this article made me think of another film, The Last Stand. This is not a western in the traditional sense, although it very much follows the rough strokes of the genre. It’s all about a lone hero who finds himself at the focal point of a “high noon” showdown, and the film highlights muscle cars and a wide variety of small arms, with lots of fast driving and straight shooting. It’s a near-perfect guy film. Let’s look at the film poster featuring Arnold as the small town sheriff. Here our hero stands tall, holding a large framed revolver. Now, this is exactly the sort of thing we associate with a western hero, but it’s also highly anachronistic because no one in professional law enforcement has carried revolvers for decades now. Also, thinking of costuming, Arnold wears a really nice looking leather jacket throughout much of the film. Done in nylon instead of the higher grade leather, this is the kind of jacket you might find on a DPS trooper – in bad weather. It’s reminiscent of a flight jacket from WW2, which carries with it all manner of heroic connotations; this is the jacket of heroes since 1944. Now, no real sheriff in a border town in southern Arizona would be wearing this, except for maybe a couple of weeks during the winter. But it fits the image, both of Arnold (who wore a leather jacket, the Schott Perfecto, famously in Terminator) and of a western lawman. The other, perhaps more startling element in the film is the weapon of choice for one of the main bad guys, Burrell. He carries a revolver once again (!), but this is a special one. Take a look: Whew! That’s some hogleg! You don’t see this gun much outside of Lonesome Dove, and that’s because it’s a Colt Dragoon. Manufactured beginning in 1848 or so, it was a powerful .44 caliber firearm very popular with the Texas Rangers and US Mounted Rifles up through the Civil War. It was supplanted by the 1860 Army model, which was much lighter and only slightly less powerful, and of course, no one except Gus McRea really carried them after the advent of cartridge guns in the 1870s. Some examples of dragoons converted to fire cartridges are extant, but they are fairly rare. So what’s a bad guy with Mexican cartel connections doing firing one at our hero in 2013? It’s simply a super-cool gun – it’s big and bad (though very carefully not as big and bad as Arnold’s revolver!) and visually arresting. What cartel bad buy wouldn’t want to carry such a bad-ass piece? People who have no knowledge in firearms will be impressed by this revolver’s “stage presence,” and those who do know what it is even more so. I think I may have squealed in delight when I first saw it in this film precisely because it was so unexpected.

So the upshot of all this is simply that while some historical accuracy is important in storytelling and movie production, a certain leeway should be expected by its viewers in the pursuit of the story. As Maxwell Scott says in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” I’ve reviewed several movies here, but not yet a book (except for talking up my own, which is still available on Amazon … just sayin’). I thought to begin book reviews with a recent effort from the incomparable Larry McMurtry titled The Last Kind Words Saloon (2014).

This latest work from McMurtry has gotten some mixed reviews, and I suppose that’s what I intend to do as well. As the Pulitzer Prize winning author of Lonesome Dove, McMurtry surely knows how to spin a tale, and his writing remains tight, his pacing solid and dialog oftentimes delightful. But what in the hell are Wyatt Earp and Doc Holiday doing in this novel?! The characters are solid, believable as far as it goes, except that they bear no – NO resemblance to their historical counterparts. McMurtry goes so far as to put them in Tombstone and in tense relationship with the Clantons and McLaurys, and yet there is no gunfight at the OK Corral, only a few hard words. The Last Kind Words Saloon is exactly why I have pause concerning historical fiction in which famous figures serve as the benchmarks or guideposts for a fictive tale. If you put a famous historical figure in your novel, he or she had better pay off for those history buffs who will read your work specifically because their favorite historical character is in it, and an author who plays fast and loose with genuine history does so at his peril. McMurtry knows this; his previous books (even Lonesome Dove) often featured real historical characters, but they were strictly walk-on parts, which kept them believable and – here is the important part – didn’t distract from the story McMurtry was telling. In Kind Words, the historical figures are the protagonists, and it is highly distracting that their narrative arc wholly ignores their actual histories. As a reader, I continued to expect the plot to weave itself into the real history at some point, but alas, the book ended without that payoff. The only exception to what I’m formulating as a rule here is when authors write speculative fiction that consciously subverts the actual history, a “what if Hitler didn’t die in his bunker” kind of scenario. I believe many history buffs give this a pass because the novel does not pass itself off as a real history of any kind, but McMurtry doesn’t give his readers any guideposts in this way, leaving them to muddle through the book on their own. The books is worth a perusal on its own merit, if only the reader can trick themselves into substituting “Bill” and “Ted” for the historical names as these original characters sally forth on their Big Adventure. Westerns are back, in full force this year, and critics can’t stop talking, not only about the individual films, but also about the cultural phenomenon of westerns making (yet another) comeback. “Back from the dead,” they all cry, as though this is an astounding feat.

It gives me some pause, as though the western genre is some redheaded stepchild that no one thought would amount to much, and everyone is amazed when one makes a good showing of itself. But there is a history to this narrative, and part of the answer to why everyone is so surprised lies in the very nature of the genre itself. Way back in the mid 1970s, a literary critic named John Cawelti wrote The Six-gun Mystique (1975), and part of his work was to declare the western dead – he writes that once a genre has been spoofed, it can no longer be taken seriously, and it will no longer resonate with audiences as it had previously. He wrote this shortly after the brilliant Mel Brooks had done Blazing Saddles (1974), and if one watches this film and considers the historical moment in which Cawelti made this prediction, it makes perfect sense. But … he was wrong. So wrong. In fact, he was proven wrong almost immediately with the release of The Outlaw Josie Wales (1976), a film that much of Hollywood thought would tank because everyone knew the western was dead, and yet it became an instant classic, and remains so today. Oh, great film. He was also wrong in a larger sense, because Mel Brooks went on to spoof the horror genre with Young Frankenstein (1974) as well as the sci-fi genre with Spaceballs (1987), which had zero affect on the success of the continuing Star Wars franchise. So the lingering question is why do so many critics, critics who likely have not read what is now an obscure reference work, seem to fall in line with his thinking? I believe the answer lies in the very nature of the western genre and its attitude toward, and treatment of death. The western invites ruminations on death and the transience of our worldly existence, and is in fact largely self-reflective about such matters by the very nature that the mythologized “West” was contained inside a historical period of roughly one generation. The heroes of our frontier were born on the cups of a created West, and lived to see it decline and be taken over by civilization – indeed; many of the frontier icons were active agents in the civilization of the west, which is perhaps one of the genre’s best ironies. The world that made people like Buffalo Bill Cody, William “Bat” Masterson, and Wyatt Earp famous was already gone long before their own deaths. Masterson died as a newspaperman in NYC, and Earp positioned himself as a Subject Matter Expert in early films, following the mythologizing example of Buffalo Bill Cody, who became a caricature of himself and turned his own biography into a commodity for Eastern consumption. In some ways, one might argue that he sacrificed his own actual history for the creation of a mythic history of the western frontiersman. The West was never meant to live on. Its demise was always already deeply embedded within its own story, and this is seen even in some famous examples of the genre. Movies like Tom Horn (1980) and Monte Walsh (1970, 2003) explicitly address the passing of the frontier and the necessity or resistance of characters to change with the times. Sometimes the movies eulogize the passing of a way of life, like the cowboy culture in the aforementioned films, or the codes of the gunfighter in The Shootist (1976), or even an entire way of life, as in Dances With Wolves (1990). So it makes some sense that the progressivism that superceded the frontier, and even appears in many of the western films that acknowledge it, would be embraced by critics. Surely, the story goes, our contemporary culture is far too sophisticated to bother with such horse operas. And yet, as critics ranging from Slotkin to White have demonstrated, the western is a highly variable genre that manages to both remain true to its benchmark traits while also reinventing itself for new audiences. So ride on, cowboy, ride on.  Patrick Wilson as Arthur, hoping to save the day and his beloved Patrick Wilson as Arthur, hoping to save the day and his beloved Well, let me say that I liked this film; I thought it a proper western. I’d heard some foul reviews from friends who thought it didn’t make the cut (pardon the pun), but in the end I thought it a well-done film that satisfied all the western genre expectations and also introduced a new twist. Bone Tomahawk has been widely labeled a “horror/western,” and I understand the impulse to do so; like its brethren Ravenous and Cowboys and Aliens, it does cross genre boundaries a bit, although in the end, I think the horrific aspect of a cannibalistic tribe tucked away in the mountains stays much closer to the traditional genre boundaries than either of the earlier films do. To address the complaints of some of my friends, who said there was one scene in particular that lost them; yes, I know which scene you mean, and I too found it gratuitous and, more importantly, pointless. Once Deputy Nick is taken from his cell, viewers know exactly what will become of him, and seeing the violent end to this character on center stage does little to forward the plot or even heighten tension. I feel it would actually have been more effective to have the tortuous action occur offscreen, allowing viewers’ imaginations to fill in the blanks. However, it is also a brief scene, and I think the rest of the film is effective enough to give it a pass. Back to its assets. One thing I think the film does really well is that by setting the antagonists as a mysterious “tribe” who are shunned and feared even by the local native tribes, the film is able to cast an “Other” as the enemy without complicating our contemporary attitudes toward westward expansion and the subjugation of native tribes. There is a small but effective scene in which a native character (played by Longmire’s Zahn McClarnon) advises the posse not to go, saying that his tribe avoids this canyon because they’re so dangerous. This effectively establishes that the tribe is not Indian, and heightens their otherworldy aspect. Had this film been made in the 50s or 60s, it would have been easy enough to make the bad guys “Indians” and be done with it, and no one would have questioned the choice. But westerns have evolved with our national consciousness, and we no longer uncritically accept Native Americans as the natural antagonist, even in a western. So Bone Tomahawk is able to deftly recast the Other as an unnatural tribe of flesh eaters, maintaining the dichotomy of hero and villain without creating the cognitive dissonance of imperialism or conquest that older westerns may have to a younger generation. Finally, this film (unlike the Hateful Eight), reifies an old genre staple and provides something close to a happy ending – well, happy for at least a couple of characters, anyway. I won’t spoil it further, but the film concludes on a fairly positive note, giving viewers a satisfying resolution. The film is gritty and even brutal, to be sure, but in the end it reifies the social construct that was disrupted by the antagonists, and finally privileges the values of heroism, loyalty, and ultimately the power of love. Over the holidays I went to the theater; I don’t often go to the real theater since the advent of Netflix and DVR, but some things are still worth seeing on the big screen, and almost anything from Quentin Tarantino is a sure bet to be a visual extravaganza. I was not disappointed. Okay, I didn’t hate it; I was trying to be clever in my title and get you to read this, but I do have some bones of contention (stay tuned for my forthcoming review of Bone Tomahawk).

To be brief: I really liked the film, BUT I don’t know if I loved it - or liked it enough to own it on DVD/blu ray/whatever comes out next. I don’t think I’d pay theater prices a second time, either, but that has as much to do with my middle-aged stay-homeness and the rich tapestry of the current crop of movies as with my opinion of this film. The Hateful Eight is Tarantino’s eighth movie, according to its introduction. I looked it up on IMdB and counted at least ten films that were exclusively his, as opposed to his writing credits, or directing television shows or the like, so I think he’s playing with viewers here. I think that’s fair. It’s visually stunning, with brilliant cinematography and a great use of setting to set the stage for his story. Tarantino does a solid job in the western genre, which almost pleads for a subtle combination of traditional storytelling and groundbreaking genre-bending. Tarantino stays close to the traditional mores here, and the cast and writing is first-rate. Because he’s Tarantino, you know it’s going to be a very graphic movie, and it does not disappoint. In fact, his graphic depictions of violence are not even new to the genre, and not because this is his second western (Django Unchained having come out two years prior) – Sam Peckinpah was shocking viewers with gritty violence back in the 1970s, and his was more realistic. It is, however, Tarantino’s unrepentant penchant for graphic – I do mean graphic – violence that finally undoes the film for me in many ways. His violence is gratiuitous and unrealistic*, and it ends up feeling like a Technicolor yawn rather than story-motivated violence. This is the problem: when Tarantino, who has clearly restrained himself for much of the film, finally lets himself loose, the tightly-woven story he was telling virtually disappears into a melee of Tarantino … well, being Tarantino. He gets in his own way in telling the story, for me, and I am jarred out of the suspension of disbelief and immediately I’m not worried about a character being shot, or hanged, or disemboweled … I’m suddenly no longer in his fictive world, but am once again sitting in a theater and thinking (perhaps with shock and dismay) at how graphic this film is. Spoiler Alert One other thing, as long as I’m grousing. The other point about the film that bothered me is that everyone dies, and frankly, I’m not okay with that. I understand that there are philosophical and narrative theories that can account for this, with omniscient third-person narrators and what-not, but I can’t shake my old university fiction professor’s admonition that if a writer kills off ALL his characters, the question remains unanswered about who lived to tell the tale? This is not a small question, and creates a lingering problem for some viewers – like myself. I concede that it’s not an insurmountable problem, and in our post-postmodern world viewers are likely unfazed by such a narrative wrinkle. Perhaps my problem is that I’m essentially old-fashioned, and I want to see someone – almost anyone - make it out of this chaotic mess alive. I want a good old-fashioned (see?) hero to rise above the violence and establish the moral certainty that grit can see you through. But Tarantino doesn’t play that game, and maybe I shouldn’t have been so surprised. *I’m not normally dissuaded by graphic violence, but Tarantino’s use of blood and exploding heads is cartoonish, almost Monte Python-esque. This is almost a signature style of his, but it worked in the Kill Bill series precisely because those movies were an homage to a B-film martial arts genre in which this approach was a better fit. |

AuthorJoin me as I postulate about literature, popular culture, martial arts, and who knows what else. Archives

July 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed