Photo from IMFDB.org

Photo from IMFDB.org I was reading an article by Lily Absinthe on the costuming of one of my favorite films, Tombstone (https://lilyabsinthe.wordpress.com/2015/05/31/). In it she predictably points out where the film gets costumes right and wrong based on actual period clothing, but where she surprises me is in her observation that moviemakers ought to be given a bit of leeway in their choices, because as she concedes, “Costuming supports this story-telling process and it’s often subject to conscious design changes in order to increase the dramatic effect.”

For reasons I dare not contemplate, this article made me think of another film, The Last Stand. This is not a western in the traditional sense, although it very much follows the rough strokes of the genre. It’s all about a lone hero who finds himself at the focal point of a “high noon” showdown, and the film highlights muscle cars and a wide variety of small arms, with lots of fast driving and straight shooting. It’s a near-perfect guy film.

Let’s look at the film poster featuring Arnold as the small town sheriff.

Here our hero stands tall, holding a large framed revolver. Now, this is exactly the sort of thing we associate with a western hero, but it’s also highly anachronistic because no one in professional law enforcement has carried revolvers for decades now. Also, thinking of costuming, Arnold wears a really nice looking leather jacket throughout much of the film. Done in nylon instead of the higher grade leather, this is the kind of jacket you might find on a DPS trooper – in bad weather. It’s reminiscent of a flight jacket from WW2, which carries with it all manner of heroic connotations; this is the jacket of heroes since 1944. Now, no real sheriff in a border town in southern Arizona would be wearing this, except for maybe a couple of weeks during the winter. But it fits the image, both of Arnold (who wore a leather jacket, the Schott Perfecto, famously in Terminator) and of a western lawman.

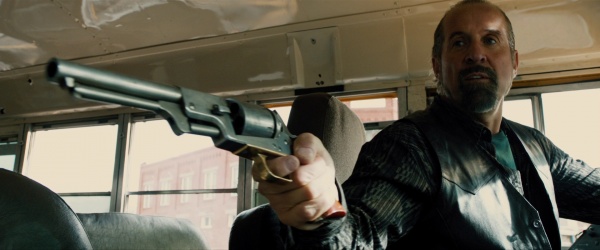

The other, perhaps more startling element in the film is the weapon of choice for one of the main bad guys, Burrell. He carries a revolver once again (!), but this is a special one. Take a look:

So the upshot of all this is simply that while some historical accuracy is important in storytelling and movie production, a certain leeway should be expected by its viewers in the pursuit of the story. As Maxwell Scott says in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed